Research by Dave Hedlund

Edited by OC Staff

Over the summer we’ll be visiting various members of the Canadian orchestral community – organizations and individuals who contribute to a thriving arts scene in Canada. If you want to write for us about your experience as an artist or arts administrator during the pandemic, get in touch with Katherine Carleton at [email protected].

While we are certainly living in unusual and challenging times, Covid-19 isn’t the first global pandemic that has struck our communities and shaken the arts industry. The Canadian orchestral landscape was much younger when the Spanish Flu of 1918 hit the country, just months after the end of World War I. Much like what we’re seeing right now, many industries, including the arts, were forced to close their doors to stop the spread of the virus.

With a founding date of 1908, the Regina Symphony Orchestra is one of a small handful of Canadian orchestras to have seen both the Spanish Flu and Covid-19. We were delighted to learn that the RSO’s historian Dave Hedlund has delved into their archives and the RSO is having a book written on the history of the RSO, including a chapter on the busy time period that saw World War I and the Spanish Flu. We’re grateful that Dave was willing to let us publish an overview of the RSO’s return to activity after the Spanish Flu, just over 100 years ago.

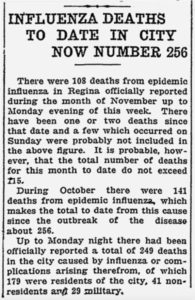

By the time the Great War officially ended in November 1918, 1200 Regina servicemen had died in the fighting. As the war was coming to a close and troops were returning to Canada, an influenza epidemic broke out across the country. In response, by October 1918, Regina stores, schools, theatres and churches were closed. Public meetings were prohibited. About 2000 of Regina’s 30,000 people were infected, according to reports in late October. By late November 2018, over 250 people in Regina had died from influenza.

An item in the Leader on Jan. 7, 1919, reported that the orchestral society was resuming rehearsals. The society “has made an occasional appearance in public.,” the paper reported, but “it has been somewhat difficult to keep the society up to desired strength during the years of war, but some additional members are now in sight and Mr. Laubach anticipates a good winter’s work.”Despite the devastation, though, by December of that year, the RSO’s founding conductor, Frank Laubach, still believed that the city needed music more than ever. Maestro Laubach promoted an opera half week for January. And the resumption of Regina Orchestral Society rehearsals was also announced.

Over the flu’s two-year reign of terror, some 50,000 Canadians succumbed, most of them young adults, compounding the effects of the war, in which some 60,000 Canadians died, mostly young men. The orchestral society, described by the Leader as “the oldest musical institution in the city,” presented a full season in 1919-20, starting on September 16th, 1919 with a performance of Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony.

And the band played on.

Learn more about the Regina Symphony Orchestra on their website or in this wonderful feature the CBC ran last year on the RSO’s 110th anniversary.

The first project the IAC consulted on was the newly created Forward Currents Festival. “Each year the festival focuses on an issue that is socially relevant to our community here in Regina”, says Gordon. The first edition in 2018 focused on Truth and Reconciliation, and the 2019 edition focused on mental health awareness.

The first project the IAC consulted on was the newly created Forward Currents Festival. “Each year the festival focuses on an issue that is socially relevant to our community here in Regina”, says Gordon. The first edition in 2018 focused on Truth and Reconciliation, and the 2019 edition focused on mental health awareness.